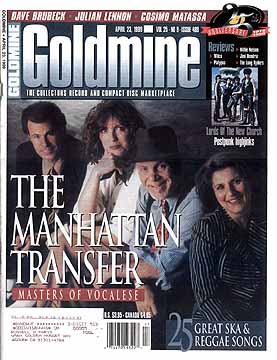

Goldmine Magazine - April 1999

|

5000 LIGHT YEARS FROM BIRDLAND: THE MANHATTAN TRANSFER

By Chuck Miller of Goldmine Magazine Their influences are as diverse as their sound. "Uncle" Charlie Lowe, the vaudeville coach. Country singer Dianne Davidson. Teen idol Frankie Lymon. Northwestern bandleader Herb Benthien. Jazz legends Jon Hendricks and Eddie Jefferson; Dizzy Gillespie and Coleman Hawkins; the Four Seasons and the Hi-Los. From those synchronous influences came the Manhattan Transfer, arguably the most respected and honored vocal quartet today. Their most recent album, Swing, debuted at #1 on the Billboard jazz charts. Another album, Vocalese, nabbed an amazing twelve Grammy nominations. They brought Brazilian music to American radio stations, brought Bob Marley and the Wailers to American television audiences, and broadened the horizons of music lovers everywhere. The story of the Manhattan Transfer is more than just Tim Hauser, Janis Siegel, Alan Paul and Cheryl Bentyne - it also includes former members Laurel Massé and Gene Pistilli. It includes collaborators Jon Hendricks and Djavan. It includes Tubby the Tuba and Doughie Duck. It includes Trude Heller's, Kenny's Castaways, the Cafe Carlyle 9 and 11 weeknights, 10 midnight and 2 on weekends. And it all began with a cab ride. Tim Hauser loves music. All kinds, all styles, all genres. He even once told a reporter for the New York Sunday News that in college, "Music meant so much to me that I even gave up chicks." He started singing professionally at age 15, formed his own doo-wop group called the Criterions, and recorded "I Remain Truly Yours" and "Don't Say Goodbye" for Cecilia Records. "I remember the first time, as a kid, when I recorded with a group called the Criterions, and I remember the first night Alan Freed played our record, on WABC, oh my God, I was in the kitchen of our house, I had just finished doing my homework, and I thought what a thrill." Two years later, he would produce "Harlem Nocturne" for the Viscounts, which later became a Top 10 hit. He spent his college years at Villanova University, and worked at their radio station, WWVV. While enrolled at Villanova, Hauser and fellow Criterion Tommy West joined the Villanova Singers, which included classmate Jim Croce. By 1963, Hauser, West and another former Criterion, Jim Ruf, recorded as "The Troubadours Three" and performed on a hootenanny multi-act tour. After some stints in the Air Force, in the New Jersey Air National Guard, and in the advertising department of Nabisco, Tim Hauser still had a strong desire to perform and sing. He left Nabisco and recruited some musicians, and named the group the Manhattan Transfer, taking the name from the title of a John Dos Passos novel. After a couple of singles, the Manhattan Transfer - which included Hauser, Marty Nelson, Erin Dickins, Pat Rosalia and Gene Pistilli (who co-wrote "Sunday Will Never Be The Same" for Spanky and Our Gang), recorded their first album, "Jukin'" for Capitol. The album was a dichotomy of styles - Hauser preferred more R&B and harmony tracks, while Pistilli (who received "featuring" credit on the album) preferred country/western and "jug band" songs. The album sold poorly, and the group broke up in 1971. Janis Siegel was no stranger to the music industry. She was still in eighth grade when she and her friends Rona Rothenberg and Dori Miles formed their own vocal trio. "The very first name we had for our group was the Marshmallows. Then we were the Young Generation." The Young Generation hired a manager, Richard Perry, and released one single on Red Bird Records, "The Hideaway" / "Hymn of Love." By high school, the group became the Loved Ones, and recorded a record on Kapp, "It's Not Going To Take Too Long" / "Diggin' You." By the late 1960's, Rothenberg left the Loved Ones and was replaced by Anita Ball. Changing their name to a lyric in a Joni Mitchell song, The Loved Ones became Laurel Canyon, and Janis switched from playing a six-string guitar to a 12-string model. "It was the era of singer-songwriters, James Taylor, Laura Nyro, Joni Mitchell was a big idol for us. We were very influenced by the songwriting of Laura Nyro and Joni Mitchell in the sense that they went out of the traditional forms of folk music, open voicings and interesting chords." By 1971, Janis split her time between Laurel Canyon and singing backup for country artist Dianne Davidson. "We were coming up when it was sort of the end of the coffeehouse era and hootenanny nights in the Village. We would play every Hoot night we could, just because it was a great opportunity to play in front of an audience. We'd play the Gaslight a lot, we played Cafe Wha, we played Kenny's Castaways. It was a very musical scene in the Village, people were always helping each other out. Then we hooked up with Dianne Davidson in Nashville. She brought us down to Nashville, and we played the Exit Inn down there, and we met a lot of songwriters. We were writing a lot ourselves as well." Besides singing and writing for Laurel Canyon, Janis Siegel did the vocal arrangements for the group. "We didn't do vocal charts - we did head arrangements. We never wrote a thing down - ever. We just remembered it. We just rehearsed. And we made an arrangement from that rehearsal, and then we remembered it." Singing ran in Alan Paul's family - his grandfather was a cantor; his parents had plenty of music in the house and played it often. Before long, 7-year-old Alan could sing all the words to standards like "Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With A Dixie Melody," and soon garnered appreciative fans in his hometown of Newark, New Jersey - the candy store owner would ask Alan to sing some show tunes to draw a candy-hungry crowd; the local barber exchanged a performance of "Rock-A-Bye Your Baby" for a free haircut. Alan later joined the Newark Boys' Club, and won a talent contest in Atlantic City by singing a show-stopping medley of "A Song And A Dance Man" / "A Quarter To Nine." He soon joined an acting school in New York City with vaudevillian Charlie Lowe. "Uncle Charlie," Alan remembered fondly, "had a studio at 1650 Broadway, down in the basement. At the time - this was in the 1950's - he was really, I think, the most successful coach for kids in New York. The thing I got out of him, more than anything else, was the rudiments of performance. He was an old vaudevillian. When I was studying with him, he was about 75 already, and his wife was in the original silent movie version of 'The Ten Commandments.' But they really had the foundation of vaudeville performance. It was the beginning of my journey into American popular music, in a sense. Because all the material we sang in was vaudeville music. So it was Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, Eva Tanquay, Russ Colombo, it was all of these songs that came from that era. He put a troupe together that I was part of, 14 of us kids, and called us the Charlie Lowe Revue. And we would go up to the Catskills in the summertime, performing in different hotels. Elliott Gould, who also studied with him, used to refer to him as Fagin. Working with Charlie Lowe was a great way to start." By age 12, Alan Paul was already a veteran of the Broadway stage, appearing in the musicals "Oliver!" and "The King and I." Even while an undergraduate at Newark State Teachers College (today known as Kean University), Alan still acted and sang - and filled in one night as a replacement member of the Lettermen. "Whenever they would have concerts at the theater, I was responsible for setup. The college had hired the Lettermen to come and perform, so I was backstage setting up the microphones and everything else. They were on the stage, and they were having an argument - it was between Tony Butala and the younger brother of one of the original Lettermen, who was brought in as a replacement. So Tony came up to me and he says, 'Hey kid, how would you like to be a Letterman for the night?' I knew their songs, so I performed with them that night." Cheryl Bentyne's singing debut impressed two of the most important people of her life - her parents. Her father, Herb Benthien, was a famous swing and dixieland bandleader in Washington State, often referred to as the "Benny Goodman of the Northwest." "That's how I learned to enjoy swing music," said Cheryl. "I was very young, my father would have jam sessions at the house, and I just walked around absorbing all the music. It just sunk into my pores. I could remember when I was really young, my mother would go out and play the piano, she had this one big stride tune she would play. So I took piano lessons, too." In 1968, Cheryl performed in a revue at her high school in Mt. Vernon, Washington. Her mother was in the audience, who up until that time, didn't know her daughter could sing. "We did this revue when I was a freshman, and I did 'I'm The Greatest Star' and all this stuff - a cappella! I didn't have charts or anything, I just came out and sang. I did the whole 'I'm The Greatest Star' from beginning to end. Hearing the orchestra in my head - and not realizing nobody heard a thing except my voice. And she came to that revue, and said to me later, 'My God! You can sing! Why don't you go sing with your dad?' So I later sang with him and his band on the weekends." After high school, Cheryl moved to Seattle and joined the New Deal Rhythm Band, mixing comedy with music, blending Isham Jones with Spike Jones. "I saw the band one night, and said to myself, 'They're insane, I would love to do this.' So I auditioned, and sang 'Big Spender' and some other schticky stuff. The guy who was fronting the band was like Groucho Marx and Cab Calloway put together. The rest of the band was a seven-piece zoot suit outfit. I worked with them for four years. We played the whole west coast, all the way down San Francisco." After the "Jukin" album flopped on the charts, Tim sustained his musical dream - and made ends meet - by driving a New York City cab for about four months. In February 1972, during a nasty blizzard, he was driving up First Avenue, looking for fares. "I had just come over the 59th Street Bridge," said Tim, "and I took the First Avenue exit uptown. And this woman hailed me on the corner, in this blizzard. Wearing a miniskirt, yet. When I was driving her in the cab, she said to me, 'You look like a musician.' "I said, 'I am, but why?'" "You just look like one. What did you do?" "I had a group called Manhattan Transfer." "And she slapped her leg in the back of the cab, and she said, 'You're one of my favorite groups!'" After the cab ride, both driver and passenger stopped at a coffee shop near the Daily News building and started talking. Her name was Laurel Massé, she had done some recording and session work around New York, and would be willing to record some demos with Tim in the future. Meanwhile, Janis Siegel's group Laurel Canyon was performing at Kenny's Castaways, a Manhattan nightclub. "We were staying at the Wellington Hotel," said Janis. "Even though we lived in New York, we wanted to stay at the hotels, too. After the show, we all went back to the hotel for our usual party. And Phillip, our conga player, had to take his own cab - he had all his drums with him. So he hailed a cab, put all the drums in the back and sat in the front with the cabbie. Who happened to be Tim." "So we got to the hotel," said Tim, "and as I'm unloading the drums, he said 'Listen, we're going to have a little band party, would you like to come out and meet the band?' So I parked the cab, we brought his drums upstairs, and we had a little band party. And that's how I met Janis. She was in a trio called Laurel Canyon, so we started talking, and this was the same thing that happened with Laurel - Janis at this party said to me, 'Are you in a group?' "I said, 'I was in the Manhattan Transfer.' "Oh, you sang Java Jive with the Edwin Hawkins Singers, on this TV show called Scene 70.' "'Yes, that's right." "She said, 'I was in the audience.'" Janis later invited Tim to hear Laurel Canyon perform at the Gaslight Cafe the following weekend. "Tim later said he was doing a recording session," said Janis, "and he needed singers to sing on spec, and would we be interested. So my partner Dori and I signed up. I showed up at his session, where I met Laurel Massé." Now they were a trio. Meanwhile, Alan Paul had landed a part in a new Broadway play called Grease, alternating between the roles of bandleader Johnny Casino and the "Teen Angel." "Laurel Massé's boyfriend was a pit drummer in Grease," said Tim. "And he told Laurel that there was a guy in the show that was thinking of leaving because he wanted to do something kind of like what we're doing. And he came down and he met with us, and heard us sing, and he said 'You guys are doing exactly what I want to do.'" Now they were a quartet. Every day, for the next six months, Tim, Janis, Laurel and Alan would practice and rehearse an act featuring classic swing and big band songs from the 1930's and 1940's, including some songs, like "Java Jive," from the original Manhattan Transfer lineup. They based their sound on the sax section of the Count Basie Orchestra, on the suggestion of Bob Bianco, a music teacher who worked with Tim and Janis and who taught the Schillinger System of Musical Composition. In June 1973, when they felt they were ready, the Manhattan Transfer re-premiered at Doc Generosity's, a bar in New York's lower East Side. "We went in there with the five songs we learned," said Tim, "and we sang them - the place went wild. So we came back two weeks later, we had learned one more song. So we sang the same five plus one more, and there were twice as many people there that they came to see us. The response was fantastic. So we looked at each other and said, 'You know... maybe we've got something here.'" Before long, the Manhattan Transfer had built their own loyal following, as fans flocked to their shows at Kenny's Castaways, Max's Kansas City, Trude Heller's on 6th Avenue, all the bars and clubs in Greenwich Village. Their performing style at the time - Tim and Alan in monochromatic tuxedos and spats, Janis and Laurel in Jazz-Age evening gowns, their voices in tight block harmony, their lyrics accented with sharp vocal gymnastics - endeared them to the New York crowds. The Manhattan Transfer would do two shows a night and three shows on the weekends, sometimes on their own, sometimes as the opening act for Charlie Mingus at Max's Kansas City. By September 1974, the Manhattan Transfer accepted an invitation to perform at Reno Sweeney's, which at that time was the largest venue in Manhattan for live entertainment. Before long, they were alternating between Reno Sweeney's and the Cafe Carlyle, and rock stars like Mick Jagger and David Bowie were waiting in line to see the Manhattan Transfer perform. "People started lining up the street every night to see us," said Tim, "and there was always some famous movie star in the audience every night. We made a demo tape and we started playing it around." One of those demo tapes found its way to the desk of Ahmet Ertegun, the owner of Atlantic Records. He wanted to sign them sight unseen, but the Transfer's manager, Aaron Russo, told Ahmet not to sign the band until he saw them perform (Russo also managed Bette Midler, another Atlantic artist). So Russo drove Ertegun to Reno Sweeney's, where the Manhattan Transfer were performing that night. "We did the show," said Tim, "and Ahmet came upstairs afterwards to the dressing room, and he said, 'I'm not supposed to talk to a group in front of their manager. It's not good protocol in business. But I can't help myself - it makes me very vulnerable, but I'll say it right in front of your manager, I want you on the label, and I want to record you.'" Tim, Janis, Laurel and Paul were elated. All the practice and hard work and dedication finally paid off - they were finally on a major record label. The band's eponymous LP (Atlantic SD-18133) contained most of the set list from their concert performances - songs that showed off their killer harmonies and their love of 20th-century music. A dance single, "Clap Your Hands," was released first, but it was the second single, a remake of the Friendly Brothers gospel classic "Operator," that gave the Transfer their first national hit. "Operator" (Atlantic 3292) took radio stations by storm - from the opening four-part a cappella intro to Janis Siegel's emotional lead vocal on the lyrics. "I remember the first time I heard 'Operator' on the radio," said Tim. "I was at a party and had left with a friend - she was driving the car in front of me, and we had gone a block from the party, drove up a little hill, and at the bottom of the hill there was a stop street. She was in front of me, she stops the car at the stop street, puts the brake on and comes running out of the car towards my car - I wonder what's wrong? And she says, 'Turn on the radio, turn on the radio!' "And I turned the radio on to the station she was listening to, and they were playing 'Operator.' That was the first time I heard it on the radio, and I thought 'Yes!' It was a thrill just to hear it on the radio, it really was." "Operator" eventually peaked at #22 on the pop charts, and another single, "Tuxedo Junction," reached #24 on the British charts. The band toured Europe and performed to enthusiastic standing-room-only crowds. During a concert in West Germany, they received a "Best New Group" award from the West German music industry. But because of the Manhattan Transfer's across-the-board music selection and their retronuevo costumes, music critics tried to pigeon-hole the band's sound into any established musical genre available. Sure they played old jazz standards, but they were having hits on the pop charts. And their first hit single was a gospel song. So the critics manufactured a genre for them. "Cabaret Rock," some critics wrote. "Art Deco Sha Na Na," scoffed others. Yet as "Operator" rose up the charts, Hollywood took notice. The Manhattan Transfer made guest appearances on various variety shows and television specials. One such television appearance was a Mary Tyler Moore variety special for CBS, called "Mary's Incredible Dream." The concept, a one-hour history of the world as performed in song and dance, allowed Mary Tyler Moore to interact with special guests Ben Vereen, Arthur Fiedler, fiddle player Doug Kershaw - and the Manhattan Transfer, as 1920's art-deco celestial sycophants. They were able to wedge a performance of "Java Jive" into the special (complete with Tim Hauser mimicking Louis Armstrong's scat on one lyric), and Alan Paul performed a solo version of the Rolling Stones' "Symphony for the Devil." "After it was all said and done," said Alan, "it was a million dollars over budget, and CBS hated it. They said, 'What is this, it doesn't make any sense.'" Meanwhile, Monty Kaye, the producer of Flip Wilson's television show, suggested that the Manhattan Transfer's singing and performing might work as a variety series. CBS executives took in two Manhattan Transfer concerts - one in Los Angeles at the Roxy Theatre, and another at New York's Bottom Line - and were suitably impressed. Within weeks, contracts were drafted and signed. The Manhattan Transfer premiered on August 10, 1975 as a 60-minute comedy-variety summer replacement series. "We had two writing teams for that show," said Janis. "Ours - and theirs. It was like Amtrak and Penn Central. Our writers were Joel Silver, Tim's sister and Bruce Vallance. That was Amtrak. And their writers kept going to this variety formula - the show needed comedy and sketch bits in it, and that included Doughie Duck." "Doughie Duck," a character created by Archie Hahn, was added to the series by the "Penn Central" writers to appeal to youngsters who normally watched The Wonderful World of Disney at that hour. Unfortunately, Doughie Duck was funny only to the writers who created him, and his catchphrase "Hey Tim!" still makes Tim Hauser cringe. "You can clearly see the delineation," said Tim Hauser. "You can see what sections came from which writers." "And then we had to deal with the censors," added Janis, "because we were on at 7:30 on a Sunday night. We wanted to do some double-entendre material, and they wouldn't let us. We couldn't do some of the songs in our catalog, like 'Well Well Well, My Cat Fell In The Well,' and 'Lederhosen,' in Jack and Jill drag." "The ratings for our show were very high on the Coasts, and very low in Middle America," replied Tim, "the Trent Lott community did not get it." "However," said Janis, "in spite of everything, we did do some wonderful things. We had Bob Marley and the Wailers on in their first United States television appearance. We had some very good comedians on, Robert Klein and Steve Landesberg. And we had some good music." Because of the lack of rehearsal time to learn new material, the Manhattan Transfer mined their catalog for over 30 different songs during the show's four-week run - they went through all their recorded material, the stuff that hadn't been recorded yet, enough music to record a new studio album every Sunday night. "We didn't want to get picked up for another season," said Tim, "because we knew that we couldn't do another season. These shows are put together in a week, and this is why television is what it is. You cannot do quality work in that short a period of time." They didn't have to worry. During the 1970's, it seemed almost any singing group with a couple of hits got their own television show, and many of them - The Starland Vocal Band Show, The Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis, Jr. Show, The Captain and Tennille Hour - lasted only a few weeks. The Manhattan Transfer lasted four episodes, and was not renewed for the 1975-76 television season, much to the delight - and relief - of the group. The Manhattan Transfer returned to the recording studio, and in 1976 released the Coming Out album (Atlantic SD-18183). Produced by Richard Perry (who previously managed and produced Janis Siegel's former group The Young Generation), Coming Out mixed more contemporary songs with the classic material that had been the Transfer's bread and butter, ranging from Todd Rundgren's pen ("It Wouldn't Have Made Any Difference") to Ringo Starr's drums and Dr. John's piano ("Zindy Lou"). Coming Out sold millions of copies in Europe, where a single from the album, "Chanson D'Amour," hit #1 in France and in England, a chart-topper on both sides of the English Channel. On the strength of "Chanson D'Amour," the Manhattan Transfer toured Europe again, including a show at the MIDEM music business convention in Cannes. In a 1977 interview, Alan Paul remembered how that song was chosen and recorded. "The song was written in 1957. We'd been recording all day and we hadn't gotten that far. Just as we were about to leave, Laurel shouted, 'Hey wait a minute, I've got an idea.' She used an Edith Piaf sound in her voice and we recorded it in one take. She wanted to get a romantic French feel behind it." The next album, Pastiche (Atlantic 19163), lived up to its name - a mixture of various musical styles and genres. By this time, the Manhattan Transfer were experimenting with more open voicings and less block harmony, adding new depth to their vocal precision. Between Pastiche's list of Cole Porter and Duke Ellington songs, the Manhattan Transfer collaborated for the first time with JonHendricks, the vocal jazz legend and one-third of the Lambert, Hendricks and Ross vocal jazz group. The collaboration, "Four Brothers," was originally written by Jimmy Giuffre for Woody Herman's Second Herd. For this song, the Manhattan Transfer replicated - using only their voices and Jon Hendricks' lyrics - the melodies of Zoot Sims, Stan Getz, Herbie Steward and Serge Chaloff, Woody Herman's sax section. Pastiche sold well in Europe, but could climb no higher than #66 on the American album charts. Tim, Alan, Janis and Laurel toured Europe, playing concerts in support of Pastiche, and listening to different music in anticipation of using some new ideas for a new album. "We had just come back from Europe," said Alan, "we were in Europe for a couple of months touring, and we were scheduled to open in the Roxy Theater in Los Angeles, and we had all these new ideas and things that we wanted to present to the public." "We were in a very high stressful period," added Janis, "in the sense that we were rehearsing a new show intensely. We were working with Toni Basil on choreography, and it was a lot of new stuff. And we were going so fast, it was literally hitting a brick wall. There were a lot of intense rehearsals. Laurel, I think, fell asleep at the wheel in her car one night - and had a bad car accident." Laurel Massé's car hit a pole. Besides a broken leg and a broken arm, the accident shattered her jaw, and it was wired shut for about three months. "When she finally came around," said Tim, "and she started getting back out into life again, she said she wanted to try a solo career." Laurel's solo career included three solo albums, and successful performances at various jazz festivals. "Laurel's still very much active," said Janis. "She's doing a lot of a cappella work, storytelling, that kind of stuff. I spoke with her a few days ago. And during the time of re-evaluation, Laurel decided she didn't want to be in the group any more. It was a very brave decision, and we had to decide whether we wanted to quit ourselves or go on. And we decided to go on." After Laurel left the group, the rest of the Manhattan Transfer had to make a decision - they knew nobody could replace Laurel Massé - but rather than post full-page cattle-call ads in Variety looking for a new soprano, they put out feelers to friends of theirs, looking for somebody who had the voice, the sass, the total showmanship and dedicated work ethic necessary to be a Manhattan Transfer member. "I remember when I was told about the auditions," said Cheryl Bentyne. "We were at the Baked Potato (a club in Los Angeles) one night, and as we were leaving, my manager looked at her boyfriend and said, 'Should I tell her?' "He goes, 'Yeah, tell her.' "I'm asking, 'What, tell me what?' "She said, 'Would you like to audition for the Manhattan Transfer?' "I stood there and screamed with joy - right in front of the Baked Potato!" "We had auditioned eight or nine other people before Cheryl," said Alan, "and they were all good. But it was the package - it's very demanding to be in a group. Not only do you need to be a good soloist, but harmonically speaking, in terms of blend, it's just something that you can't even teach anybody. It's something that you have to hear." The tryouts were held at Janis Siegel's house. For the audition, Cheryl rehearsed two Manhattan Transfer hits, "Candy" and "You Can Depend On Me." In case she needed a deal-clincher, she also learned "Four Brothers." "We spent a whole day at Janis' house," said Tim, "we had listened to two other people before that. And Cheryl came in - she had driven by Janis' house about an hour before she came in, she was so nervous, she had been a big fan." Janis offered Cheryl a cup of herbal tea to sooth her nerves, and Tim and Alan chatted with the new recruit. During the audition, Cheryl performed both "Candy" and "You Can Depend On Me" flawlessly, and even sight-read "Snootie Little Cutie" without a hitch. "Just as soon as we started singing," said Tim, "I saw Alan's eyeball kinda move over to my right, and I looked at Alan, and Alan and I - the eyes were communicating, because we were singing. But as we're singing, he's looking at me, I'm looking at her - this is it, this is it, and we looked over at Janis, and Janis was nodding this was it, and we sat down afterwards and spent about two hours just talking with her. And afterward, Cheryl said to us, 'I wondered, after we were done singing, why you guys just wanted to keep me around?' It was because we all knew, without even looking at each other, that we had decided to add her to the group." Immediately the Transfer began work on their next studio album. Jay Graydon, a session guitarist who played on Pastiche, was recommended as a producer by the Transfer's sax player Don Roberts. Although the group still had success in Europe, they hadn't had an American radio hit since "Operator" five years earlier, and it was time to let people know the Manhattan Transfer were no longer deserving of the "cabaret art deco" description that critics fostered upon them. "For us, Extensions was a very radical move," said Alan Paul. "It was a new group, with Cheryl in. And we had decided, for that album, we really wanted to try and break America. We had a lot of success in Europe, the 'Coming Out' album was very successful. But we were frustrated because we weren't really getting the notoriety, the success that we felt that we wanted in the homeland." The hard work paid off, as Extensions (Atlantic SD-19258) became an across-the-board hit album. A melange of styles and musical genres, the album's tracks deftly bounced between jazz, pop, dance, vocalese and a cappella, showing fans the dexterity of a group unfairly labeled as cabaret pop. Extensions also became a hit on college radio stations, whose programmers thought the Manhattan Transfer were a new wave band, based on their futuristic wardrobe from the album cover. Even music teachers appreciated Extensions - many of them used that album in conjunction with Coleman Hawkins and Charlie Parker albums in music appreciation and jazz history classes. One track on Extensions, "Body and Soul," was a tribute to the great vocalese singer Eddie Jefferson. Jefferson had performed a version of the Coleman Hawkins classic, replacing Coleman Hawkins' saxophone with specially-crafted lyrics, emulating what the saxophone could say if it spoke English. "I wanted to do 'Body and Soul,'" said Tim, "because I thought boy if we could whack through Coleman Hawkins, we would be saying something. Eddie was the one that did the original vocalese, and he said 'You guys can't do that. I always wanted a group to do that song, but it can't be done.' "I said, 'It can be done, man.' "He said, 'You can't do it.' "'We're going to show you.'" Unfortunately, Jefferson never got to hear the Manhattan Transfer's tribute to both him and Coleman Hawkins - a few days after he spoke with Tim about the project, Jefferson was murdered. When the Extensions album was released, it was dedicated to his memory. The Transfer sang Coleman Hawkins' sax part with Eddie's lyrics - then they and Richie Cole wrote new lyrics at the end, paying tribute to the grandfather of vocalese. Four singles were released from Extensions - a remake of the Videos' hit "Trickle Trickle," a vocalese interpretation of Weather Report's "Birdland," an original composition, "Nothin' You Can Do About It" - and a dance track co-written by Alan Paul, "Twilight Zone / Twilight Tone." "Twilight Zone was a big disco hit," said Cheryl. "We would go into these discos in Europe, and they'd be playing our song, and the staff would surround us and give us the VIP tables." "We could have had a Top 3 record with 'Twilight Zone,'" said Tim, "because it had hit #1 in New York and #2 in LA, but what happened was there was a disco rebellion - KC of the Sunshine Band talks about that in his VH1 special, to the death of disco, the Disco Demolition Night in Comiskey Park. 'Twilight Zone' got banned from the radio in the midwest because of its disco beat. In Chicago, they wouldn't play it at all. When you take that zero, and add it to the 1 and 2 on the coasts, you've got a #30 national charting. But if we had gotten the same play as we had gotten on the coast..." Nonetheless, the Manhattan Transfer reappeared on television, this time as guest performers. In March 1980, they showed up on American Bandstand, blasting through "Twilight Zone" for an appreciative Dick Clark. They performed "Trickle Trickle" on Solid Gold, one of the few times when the artists stole the cameras' attention from the scantily-clad Solid Gold Dancers. That year, the Manhattan Transfer picked up their first two Grammy Awards, as a track from Extensions, "Birdland," won both for Best Jazz Fusion Performance, and for Best Arrangement for Voices (awarded to Janis Siegel). "Birdland" was written by Josef Zawinul for his band Weather Report, and was updated with lyrics by Jon Hendricks. Earlier that year, Atlantic wanted to release "Birdland" as a single in the UK, but they needed it edited down for single release - and needed it immediately. Rather than let some union-scale tone-deaf engineer mis-edit the song, Tim took a cassette copy of "Birdland," and created a single edit using the pause button on his double-deck tape machine. "I took it back home," said Tim, "and I patch-keyed around with it for about an hour, and came up with that edit. And that was the one that won the Grammy, was the 45 RPM version. 45 RPM - remember that? Vinyl! Big hole in the middle! That was it." If Extensions was their breakthrough album, their next LP gave the Manhattan Transfer their next big push. The title, Mecca for Moderns (Atlantic SD-16036), came from a 1952 Duke Ellington live album describing New York City's Blue Note club as "a haven for the smart set - a mecca for moderns." Not only did the album go platinum and top the charts worldwide, Mecca for Moderns became the first album to win Grammy awards simultaneously in both the jazz and pop categories. Their remake of the Count Basie Band's "Until I Met You (Corner Pocket)" won for Best Jazz Fusion Performance, their second consecutive Grammy in that category. Gene Puerling, who arranged the Manhattan Transfer's a cappella performance of "A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square," received a Grammy for Best Vocal Arrangement. And their remake of the Ad Libs' 1965 classic "Boy From New York City" (Atlantic 3816) won for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group. "I loved that song, 'Boy From New York City,'" said Janis Siegel. "I always loved that song, and it seemed like a no-brainer to include it on one of our albums. I remember Alan was also very adamant about doing that song. And Alan wrote the vocal arrangement - we didn't want to change it too much, because you want to keep what makes the record great. But our producer, Jay Graydon, changed it enough to make it our record." The song became the Manhattan Transfer's first Top 10 pop record, eventually hitting #7 in the autumn of 1981. "One morning," said Tim, "I had to go somewhere really early from my apartment, and I was not in a very good mood. I was in my car, I had gone about a mile from my apartment, I was at a traffic light, and this old guy pulls up next to me, he's got his windows down, he hadn't shaved, and he looked really funky - and his car was funky - and he was sitting staring straight ahead, like he probably didn't have his first cup of coffee either, and the radio was cranked up in his car, and all of a sudden "Boy From New York City" comes on - in his car, and he had it on so loud I could hear it - and the guy didn't move. He didn't blink an eye, he was sitting there like a statue. And I'm looking at him, and he's just stoically staring straight ahead, with all his beard stubble, and I'm hearing this record and I started laughing. I cracked up, I just started laughing hysterically. Made my day. When I think of 'Boy From New York City' and hearing your record on the radio, I always think of that incident." While Atlantic kept the Manhattan Transfer name in the public eye by releasing a greatest hits LP (which eventually became their first gold LP), Cheryl, Janis, Alan and Tim began work on a new album, Bodies and Souls. Atlantic wanted another hit, something that would capture radio stations the way "Boy From New York City" did. So the Manhattan Transfer placed all the infectious pop-hits-to-be on the "Bodies" side of the LP, and reserved the "Souls" side for the jazz and vocalese productions. Their first single released from Bodies and Souls, "Spice of Life" (Atlantic 7-89786) was co-written by Rod Temperton, whose previous credits included "Boogie Nights" for Heatwave and "P.Y.T." for Michael Jackson. Stevie Wonder even added a harmonica solo to the bridge of "Spice of Life." Atlantic promoted the record heavily, sending promo copies of "Spice of Life" to stations almost every week. The song hit the Top 40 - peaked at #40 - and fell off the charts. Two more singles were released from Bodies and Souls, but neither "American Pop" (Atlantic 7-89720), with special guest vocalist Frankie Valli, nor "Mystery" (Atlantic 7-89695), with Janis Siegel's emotion-dripping vocals, made any chart impact. And although the foursome worked their magic with Jon Hendricks on the Benny Goodman hit "Down South Camp Meetin'," earned another Grammy with the track "Why Not! (Manhattan Carnival)," and paid tribute to Theolonius Monk in "The Night That Monk Returned To Heaven," Bodies and Souls did not sell as well as Mecca for Moderns or Extensions. "I think we all felt that as a pop record, we had a very good shot," said Tim. "But the record just didn't do diddley-squat in America at all. And yet, out of it, 'Mystery' was the biggest turntable hit we ever had. That record got so much airplay and didn't sell diddley-squat. But in Japan - we had done a television commercial for Suntory Brandy. And the album was made part of that whole promotion. So the album sold incredibly well in Japan, thanks to the exposure from the commercial." The next album was a mixture of live and studio recordings called Bop Doo-Wopp. The record started off with the Manhattan Transfer's Grammy-winning rendition of "Route 66" from the motion picture Sharkey's Machine, and continued through rare doo-wop songs that were originally recorded by the Capris, the Avalons, the Four Vagabonds and the Harptones. They even took the original 1976 rhythm track of "My Cat Fell In The Well (Well! Well! Well!)," and added a new vocal track. But Bop Doo-Wopp barely dented the album charts, and none of the singles reached the Top 40. "It was the lack of success of Bodies and Souls and the frustrating sales of Bop Doo-Wopp," recalled Tim. "I don't want to put the record company down, but you're encouraged to do something very commercial - to do a pop record, and we did it and we certainly tried our best. And it cost a lot of money, and it was very unsuccessful, and it was very frustrating for us. So the attitude at the time was - why don't we do what we do best?" Ever since the Pastiche album, the Manhattan Transfer have collaborated with vocal legend Jon Hendricks. Jon crafted skillful lyrics to instrumental songs like "Four Brothers" and "Birdland," and along with Eddie Jefferson, is one of the most widely admired and respected experts in the field of vocalese. "We were talking about doing different kinds of music for years," said Tim. "This Lambert, Hendricks and Ross tradition of vocalese was what we did best, and we were certainly the best at it out there at the time." "We had talked to Jon Hendricks about this project," said Alan, "actually, Jon had spoken to us for a long time, for about three years about the possibility of doing a project together. After Bodies and Souls, we put out Bop Doo-Wopp, and we were trying to figure out what to do. It was amazing how the process happened, too. I remember we met at Janis' apartment in New York, and we spoke to Jon, and we all had lists of songs. It happened. When we usually work on an album, it takes a long time to pick the material. We had all the songs selected for the album in an hour." Hendricks believed so much in the Manhattan Transfer's project that he took a year-long sabbatical from his own performance schedule to help out with the record. In 1985, the Hendricks-Manhattan Transfer collaboration produced the album Vocalese (Atlantic 81266), an entire tribute to that style of recorded music "Jon Hendricks is incredible," said Alan Paul. " We learned so much from him. Especially when we dove into the Vocalese album. He would say things to us, from his perspective as a singer and as a writer, about how to approach vocalese. 'When you're approaching doing a solo,' he said, 'the most important thing is to go back to the source. Go back to the beginning, listen to the instrumentalist, listen to the essence of what that player was trying to express with his music, and that's what you need to express in your voice.'" "And as a lyricist," added Cheryl Bentyne, "he would say the lyrics are the last things to worry about. Don't worry about them, they will come. Because some of his lyrics to this day - there's twists and turns that he even admits he can't sing. They just fit, it works. I don't know how he gets the ideas, they come from another place. He said, 'Get the instrument, and the lyrics will follow.'" The tracks selected were not easy ones to record for any group, but the Manhattan Transfer rose to the occasion. Not only did their melodies have to match the original jazz solos, but even the inflections had to be matched - each lyrical twist as distinctive as the fingering on a sax. The group that once took their harmonies from the sax section of the Count Basie Orchestra now sang with that same orchestra on Basie's "Blee Blop Blues." Just as the Count Basie and Duke Ellington bands once combined their talents on the track "To You," the Manhattan Transfer joined their voices with another jazz harmony group, the Four Freshmen. Vocalese was a jazz lover's delight - Richie Cole and James Moody, Dizzy Gillespie (on "Sing Joy Spring"), and an all-star spin on the Dizzy Gillespie classic "Another Night In Tunisia," featuring the Manhattan Transfer, Jon Hendricks and Bobby McFerren. Alan Paul replicated Butter Jackson's trombone solo in "To You"; Janis Siegel blended Clifford Brown's trumpet solo with Tim Hauser's Harold Land tenor sax in "Sing Joy Spring;" Cheryl Bentyne added her voice to Benny Bailey's hard bop trumpet in "Meet Benny Bailey." Vocalese was also their first album with an accompanying video package. For an extra few dollars, fans of the Manhattan Transfer could purchase a VHS or Beta tape containing five music videos from Vocalese (including one video clip, "Blee Blop Blues," in which the Transfer paid tribute to the "I Love Lucy" show, starring Alan and Cheryl Ricardo, and their neighbors, Tim and Janis Mertz). When the 28th Annual Grammy nominations were announced, the Manhattan Transfer were pleasantly surprised - Vocalese nailed 12 nominations, at that time the second-most honored album in pop music history (surpassed only by Michael Jackson's "Thriller"). And when the awards ceremony took place, Vocalese brought its creators three Grammys - the Manhattan Transfer won one Grammy for Best Jazz Vocal Performance, Duo or Group; and the track "Another Night In Tunisia" earned two other Grammies - one for Jon Hendricks and Bobby McFerren for Best Male Jazz Performance, and one for Cheryl Bentyne and Bobby McFerren for Best Vocal Arrangements for Voices. The Manhattan Transfer's follow-up, the 1987 album Brasil, allowed the band to explore new horizons, bringing the pop music of Sao Paolo and Rio de Janiero to America. Top Brazilian songwriters such as Milton Nascimento, Ivan Lins, Gilberto Gil and Djavan, all contributed songs of life and love along the Amazon to the album. Brazilian musicians like Djalma Correa and the group Uakti also appeared on the tracks. The next time the Grammy awards were handed out, Brasil won a Grammy for Best Pop Vocal Performance, Duo or Group - the first time a Manhattan Transfer album, not just a single track, won a pop Grammy. One of the tracks on Brasil, "Soul Food To Go," a duet between Tim Hauser and Brazilian songwriter Djavan, received major airplay on adult contemporary stations. The English lyrics for "Soul Food To Go" were written by, of all people, former Knack frontman Doug Fieger. "Doug Fieger had been over to my house visiting," said Tim. "He was trying to be friendly, and I said, 'We got a couple of songs here, and we've got to get writers to do them.' We just came back from Brazil, and we've been talking to Djavan over dinner, and Djavan said, 'The way you want to write my material, my suggestion is when you listen to my tunes, when you hear an English word that sounds like a Portuguese word that I'm singing, write that English word down and then just keep listening until you hear another English-sounding word. Then connect the words by a stream of consciousness, try to find the relationships through abstract thinking.' "And both Doug and I found that very interesting. And he said, 'Can I take a crack at that?' "In my mind, I'm thinking 'Come on, Doug....' But I said, 'Sure, why don't you take a crack at it?' Never really believing anything was going to come of it. "So he calls me up about five days later, and he says, 'I got it!' "I said, 'You got it? You did it?' "He said, 'I got it! It's called "Soul Food To Go!"'" "I said, 'Wow! What a cool title!' "And he brought it over, and I was absolutely floored when I heard it. I said, 'This is great! And you did it in five days?' "He said, 'Yeah! Give me another one!' "So we gave him another one, and he wrote 'Zoo Blues.'" The Manhattan Transfer continued recording and performing as the 1980's drew to a close. They appeared at the Newport and Playboy Jazz Festivals; and won "Best Jazz Vocal Group" in the down beat and Playboy polls every year from 1980 to 1990. In 1989, the Manhattan Transfer was part of an all-star release called "Rock, Rhythm and Blues," a Richard Perry-produced album featuring contemporary artists taking a spin on hits of the 1950's. Included among the remakes by Rick James, Christine McVie, Michael McDonald and Elton John was the Manhattan Transfer's "I Wanna Be Your Girl," a remake of the old Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers hit "I Want You To Be My Girl." Tim Hauser saw Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers in 1956 in Asbury Park, New Jersey, when he went with some friends on a triple date. "It was an extraordinary experience. There were three couples, we were going to the show in Asbury Park, I was so excited in the paper they were coming, they were my favorite band. And we went to the show, and we were dancing, and a fight broke out in the middle of the floor." Suddenly Tim heard bottles breaking - he knew that meant glass bottles were becoming shards for a rumble between two rival gangs. "I got pushed up against the stage by the crowd. So I climbed up the stage, to avoid getting hurt. And a stagehand grabbed me and pushed me through the curtain to protect me. I go through the curtain, and I'm there by myself - I knew the building, it wasn't a strange place. I knew the inns and outs of the dressing rooms of the Convention Center from Boy Scout Jamborees and things." So Tim went towards the dressing rooms. "A little guy comes over to me, he's got makeup cradled in his hands, and he says to me, 'Do you know where the dressing rooms are?' It was Frankie Lymon! "I said to Frankie, 'Yes I do! Let me show you!' "So I showed him the dressing rooms, and he said, 'Thanks. I'm Frankie. You want to meet the guys?'" Within minutes, Tim Hauser was in the dressing room with his favorite band, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers. "The two guys I ended up talking to the most were the two surviving members of the band, Herman Santiago and Jimmy Merchant. We were talking about racial shit and stuff like that, and music of course, and then they all came in - there was the five of them and me, and nobody asked me to leave! "Afterward, some guy knocks on the door and says, 'It's time!' So they put on the white sweaters with the red T and they stood up - in this little room and sang, 'I Promise To Remember.' And I went, 'O my God....' You're not hearing it on a record or in the audience - it was as pure as if I was one of the Teenagers. I felt this music the way it really was - and it was a powerful experience. It was like God said to me - 'There's your gig, pal.'" "Years later," asked Alan Paul, "when you met them, when you mentioned that story, did they remember it?" "Jimmy says he remembered it, because there was a fight in the crowd, and it was something you remember because the show was stopped for an hour because of the fight. That night, after the show, I told my friends, and they didn't even believe me!" In 1991, the Manhattan Transfer moved from Atlantic Records to Columbia for two albums. The first, The Offbeat of Avenues, offered fans something new. For years, fans had enjoyed their vocal efforts; now Alan, Cheryl, Tim and Janis offered their fans a taste of their songwriting abilities. "Sassy," a track from the album with lyrics by Cheryl Bentyne and Janis Siegel, earned a Grammy for Best Contemporary Jazz Performance. But despite the addition of "Blues for Paolo," a Hendricks-ized version of the old Miles Davis recording, The Offbeat of Avenues did not have the staying power of either Vocalese or Brasil, and did not sell as well as expected. By this time, the individual members of Manhattan Transfer were testing the waters with their own solo projects. Janis Siegel had already released two solo LP's, Experiment in White (1983) and At Home (1987), and collaborated with Fred Hersch on two others, Short Stories (1989) and Slow Hot Wind (1995). Cheryl Bentyne's solo project, a collaboration with composer/trumpeter Mark Isham called Something Cool, was released in 1992. The group collaborated on swing hits like "Choo Choo Ch-Boogie" for the film A League of Their Own (in the movie, you can hear them singing as Geena Davis and Lori Petty are running for the train). All four members worked on other soundtracks including Swing Kids (Janis on "Bei Mir Bist Du Schon"), Dick Tracy (Janis and Cheryl, on "Back In Business"), Mortal Thoughts (Cheryl, on the title track), and The Marrying Man (Alan singing "You're Driving Me Crazy [What Did I Do?]" and duetting with Tim on "Mama Look A Boo Boo"). "As a soloist," said Janis, "you get to develop your own personal world view, in the musical sense. You get to work with other people, you get to explore different ways of working, and you get to really develop your own persona. I think you bring this energy into the group with you, and then you can suggest different ways of working within the group. Sometimes you get locked in, especially with four people." One year later, the Manhattan Transfer released their first Christmas album. Produced by Tim Hauser and Johnny Mandel, The Christmas Album featured holiday songs old and new, from the classic "Silent Night" to the Lennon-McCartney number "Goodnight." They even brought in Tony Bennett to join them on "The Christmas Song." Included in the concert tours and promotional appearances in support of The Christmas Album was a guest starring role on the television series Home Improvement. On the show, the Manhattan Transfer appear on the fictional series Tool Time, and are introduced by host Tim "The Tool Man" Taylor and his long-suffering assistant, Al Borland. Tim Taylor: I always wanted to know. Who is Manhattan and who is Transfer? (audience laughter) Tim Hauser: Yeah right, right. Now that's the name of the group, Tim. Come on. We have our own names. Tim Taylor: Oh yeah, just like the rest of us would have. (audience laughter) Janis: I'm Janis. Cheryl: I'm Cheryl. Tim Hauser: I'm Tim. Alan Paul: I'm Alan. But you know people sometimes call me Al. Tim Taylor: [To Alan] Tim and Al. Do you assist Tim? Alan Paul: I don't think so, Tim. (huge audience laughter) During the show, the Manhattan Transfer sang an a cappella version of "Santa Claus is Coming To Town," much to the delight of the Tool Time audience. It wasn't Neil Simon, but it was a long way from Doughie Duck. Their contract with Columbia ended in 1993, and before they re-signed with Atlantic, the Manhattan Transfer dove into a new recording project - a children's record. The Manhattan Transfer Meets Tubby The Tuba (Summit DCD-152) retold the 1945 George Kleinsinger / Paul Tripp stories of Tubby, an insecure tuba looking for his own melody. With orchestral support from the Naples (Fla.) Symphony, Cheryl, Janis, Tim and Alan were the narrators, and even voiced many of the characters, of the Tubby stories. "We were between contracts," remembered Tim. "And we got contacted by this small label down in Florida that wanted to do Tubby the Tuba. I loved Tubby the Tuba as a kid. Paul Tripp and George Kleinsinger put it out as a 78 album for kids. But because the technology in those days, there wasn't enough space on a record to accommodate the whole thing. So ours was really the first time all the stories in their entirety were ever presented. With the CD, you can put that much stuff on. They did the music down in Florida with the Naples Symphony, and they brought it up to New York, and we cut it at Motown Studios in Hollywood, and we practiced with our characters and our script, and we went in. Janis was eight months pregnant at the time, so she had to lie on the floor a lot to rest. So inbetween takes, she had pillows and was lying down. We had a little booth set up because we had to be able to see each other as we read the script. So Janis was over to my left a little bit, and she was lying on the floor. But we had a lot of fun doing that. We never performed it live - this arts group up in Ashland, Oregon were thinking about having us come up and do it. We still have the script and all." By 1995, the Manhattan Transfer had returned to Atlantic, and were working hard on a new album, Tonin'. Each track on Tonin' was a classic pop song, and each track had the Manhattan Transfer performing with a guest vocalist. James Taylor joined the band on "Dream Lover"; Chaka Khan guested on "Hot Fun In The Summertime," and Frankie Valli (who sang with the Manhattan Transfer on "American Pop" from the Bodies and Souls album) aided his new "Four Seasons" in a rendition of "Let's Hang On." For a cappella fans, the Manhattan Transfer even tossed in a sweet version of the Beach Boys' "God Only Knows." In an interview with Lizzy Evans, Cheryl Bentyne remembered working with Laura Nyro on one track, the Delfonics' hit "La La Means I Love You." "I remember hearing Laura Nyro, thanks to my cousin Annie, years ago and she amazed me -- so haunting, so emotional and so out of context with the rest of pop music. I decided that if I could have my dream come true it would be to sing with her, although I thought it might be too crazy of an idea. Then she played a rare concert in L.A. and Janis and I went backstage nervously to meet her and she was as sweet as could be. During the show, she was noodling on the piano and did a tiny bit of 'La La Means I Love You.' Somehow it stuck in my mind. We had all tried to find the right Philly-style song for this album, so when I thought of finally approaching Laura, this Delfonics song seemed to be perfect. In the studio in New York she just sat at the piano and brought in her own style of temp and harmonics. It was just what we wanted." 1997 saw the release of Swing, a pure tribute to the music of the 1930's and 40's. Each track on the album, from "Stomp of King Porter" to "Sing Moten's Swing", to performances with the country band Asleep at the Wheel, show the Manhattan Transfer's love of music - and the hard work it took to convey that sense of admiration on every track. Even before the first album was ever released, the Manhattan Transfer have sought true vocal perfection. Even if it meant practicing songs for weeks, every note had to be right; every inflection and timbre and vibrato had to match perfectly. "Sometimes if we work on a song and perform it live, we can perform it as we're learning it. That can be like a week or two weeks. But in recording, it depends on the difficulty of the piece. It depends on the nature of the harmony. Something like 'Sing Moten's Swing,' this is our bread and butter. It doesn't take long. Something that has more open voicings, where everything has to be really exact in tune and blended, and everyone's maybe in a different part of their voice." "For 'The Stomp of King Porter,'" added Tim, "we woodshedded it at Cheryl's, so I remember how we were going. We got through the whole chart in a week." "Before that," said Janis, "it took me five to six hours to write the vocal chart." "We worked four or five hours a day on that song - " "And we broke it up with a couple of other tunes," replied Cheryl. "So we spent about 5 hours to write it, it took about 10 hours to learn it - and probably another four hours to go over and polish it after we learned it. It's like muscle memory in sports. The more you keep doing it, the more it just becomes part of you. As you get more into the tune, you lose the thinking aspect of it, and as you're doing it, you're kind of watching yourself doing it, that way you can polish it. In those 10 hours, we could sit there and go from Bar 1 to Bar 60, and get through the tune, and then there's going over it and going over it. And when we cut to he track, you do it three or four times rehearsing it with the band at soundchecks, and then you try it the first time live - and by the fourth or fifth time you do it live, it locks in and then you're home. It's quite a process." "The thing about writing a chart like that," said Janis, "for me, a lot of my time was not spent with pencil to paper. It was spent thinking about how it was going to work, about how I was going to adapt the Benny Goodman Orchestra to voices. And who was going to play different parts." Swing also allowed the Manhattan Transfer to explore and re-interpret songs from their own performing career - including "Java Jive," "Down South Camp Meeting" and "Choo Choo Ch-Boogie." The band's hard work and dedication paid off, as Swing debuted at #1 on Billboard's jazz album chart, and sold enough CD's, tapes and albums (yes, Swing was also released on vinyl) to stay in the Top 20 of the jazz chart for an entire year. But while the pop charts and radio stations embraced the new retro swing music from the Brian Setzer Orchestra, the Royal Crown Revue and the Cherry Poppin' Daddies, the Manhattan Transfer's dose of pure swing music seemed lost in the shuffle. Atlantic barely promoted the album, and many adult contemporary stations were still playing "Choo Choo Ch-Boogie" from the A League Of Their Own soundtrack, rather than the new version from Swing. Despite the record's year-long run atop the jazz charts, Swing only sold 200,000 copies. As the band reaches their 30th anniversary in the recording industry, the Manhattan Transfer have been honored by the peers in their fields - not just with Grammies, but with acknowledgment of their contribution to music. In September 1998, they performed at the opening of the Kansas City Jazz Museum, a concert that included Ray Charles, George Benson, Patti Austin and George Duke. "We had all these giants of jazz on one stage," said Kansas City major Emanuel Cleaver to reporter Drew Wheeler. "I don't think there's ever been anything like that since the 1930's." One month later, Tim Hauser was on hand to accept the Manhattan Transfer's induction into the Vocal Group Hall of Fame in Sharon, Pennsylvania. "It's nice to feel that you've made that kind of contribution," Tim said to reporters at the time. "It's a great feeling. My children can walk through and get off the way I got off listening to all this stuff for all these years. I started listening to vocal groups since 1954, started collecting in 1955. I think I've heard them all. In the first induction class, it's a great feeling." They've also found time to pay tribute to those who helped them through the years. In 1988, they performed "Birdland" as part of an all-star concert celebrating Atlantic Records' 40th anniversary. During that same show, Alan and Tim performed "Mack the Knife," a tribute to another Atlantic artist and one of Alan Paul's inspirations, Bobby Darin. In 1996, they sang for Jon Hendricks' 75th birthday at Lincoln Center, performing "Four Brothers" and "Ray's Rockhouse." And in 1997, they performed with Tony Bennett, Clark Terry, Milt Jackson, Roy Hargrove and Shirley Horn at a tribute to jazz guitarist Oscar Peterson. "When people ask me, 'What's your greatest influence,' who knows?" replied Tim. "There are moments that can affect you. There are things that affect you that sometimes you don't even know - when you prepare some music, when you get an idea, you lay out an arrangement, when I sing on stage, certain notes, certain ways - Igor Stravinsky said, 'Amateurs imitate, professionals steal.' There are people that get their stuff from us, we get our stuff from other people. It's just the way it is. It's wonderful music." Later this summer, the Manhattan Transfer will return to the recording studio and begin work on a new album, their final one under their Atlantic contract. "We had originally planned on doing a jump blues album," said Tim. "It would have been an adult-contemporary focused record, because the Swing album was a pure approach to swing, and it wasn't a dance record. There was no money spent on promotion, the record just went out there. The jump blues album would have been an extension of the Swing album, with more post-war songs and R&B orientation - but it came to our attention that we were facing the same support problem. Acts like ours really no longer garner any interest with large record companies. Let's face it - we're out there, we sell out buildings everywhere we go, but we're over 40, over 50, and as far as record companies are concerned, we are not worth that promotional investment. So we said screw it. We're going to go into the studio and do Vocalese II. And we'll take care of ourselves spiritually in making the record, and we're not going to concern ourselves about whether it's promoted or not. The record will come out and stand on its own. We always do good work, because we try to do our best. And that's our last Atlantic album. As far as dealing with the big major corporations, I don't know if we're going to do that any more. It really only works for the big corporation, and for folks like us - we're just going to do it a different way." Through three decades, the Manhattan Transfer have remained business partners and good friends. When times were tough, they could always count on each other. "You don't push the buttons," said Tim, "and every one of us knows that there's no such thing anymore as an accidental button push. You don't push the buttons - because you know what the response is going to be. This is a very good lesson for people in relationships. When you've been together a long time - everybody's got something that's going to piss them off if you say it. And you know it. Because it's human. If you want to keep the peace, you accept the vulnerability and don't push the button. And then you stay together." "Our relationship, because it's artistic, is so multilayered," said Cheryl. "We're friends, a lot of different dynamics will come out at different points in our relationship. This is the longest relationship I've had with anyone in my life, other than my parents. For all of us, we've been together longer than we've been married - longer than we've been single." "We've been together so long," said Janis, "we're so sensitive to each other, if anybody's having a rough time, we're all affected. It can be so subtle, but we all catch it. If someone doesn't feel good or someone has a bad day or someone misses their family, we're all immediately affected. We can't go through one song without asking the affected person, 'Is everything okay?'" "We're kind of like a microcosm of life," added Alan. "We'd make good ambassadors. Ambassadors of harmony." Author's notes: This article consists of two separate interviews with members of the Manhattan Transfer. Tim Hauser was interviewed in October 1998, during the weekend of the Manhattan Transfer's induction into the Vocal Group Hall of Fame in Sharon, Pennsylvania. The entire Manhattan Transfer lineup - Tim Hauser, Alan Paul, Janis Siegel and Cheryl Bentyne - were interviewed in January 1999 between shows at the Blue Note in New York City's Greenwich Village. The assistance of Dana Pennington in coordinating the Blue Note interview is greatly appreciated. Other sources of information came from the Manhattan Transfer Fan Club, and their assistance (including Fan Relations Coordinator Dana Atteberry) is warmly acknowledged. Readers wishing to join the Fan Club may send a request to: Manhattan Transfer Fan Club, P.O. Box 1, West Salem, Illinois 62476, or contact the fan club on the Internet at www.tmtfanclub.com. This article is dedicated to the teachers and staff of the Street Academy of Albany, who inspired me to pursue two dreams - writing and music. |